幻聴・幻視などの幻覚、とくに幻聴は統合失調症の患者さんに多くみられる症状ですが、

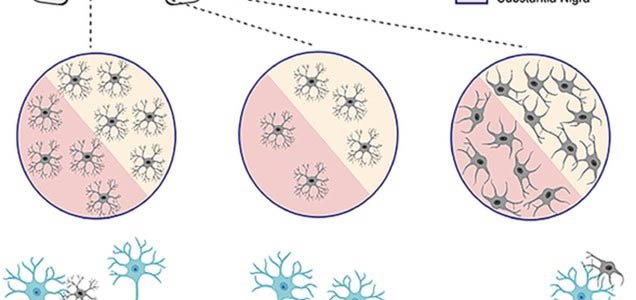

パーキンソン病 (Parkinson's disease, PD) などでドパミンアゴニストなどを内服している患者さんにもよく起こります。

それらの症例の共通点としてドパミンバランスの異常があるので、幻覚はドパミンバランスの異常が関係していると考えられてきました。

ただ、それを実験系で証明するのはちょっと難しいと思われてきました。

だって、ネズミさんに「あなたは幻聴が聞こえましたか?幻視は見えましたか?」って尋ねる事はできないですし、何を持って「幻覚」と評価するのか、という高い壁がありました。

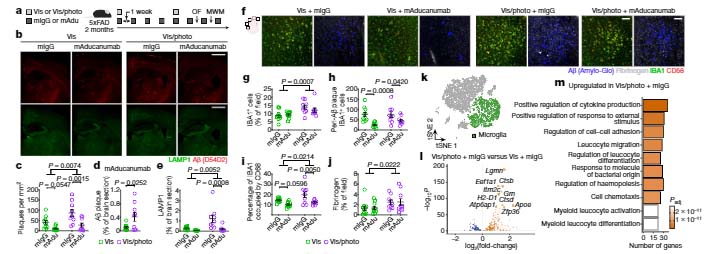

今回、アメリカ・コールドスプリングハーバー研究所のDr. Schmack、Dr. Kepecsらの研究グループは、試行錯誤してマウスの「幻聴」を評価し、

線条体のドパミンが幻聴を介在している、という内容を報告しました[1]。

マウスの幻聴を評価する実験系を確立

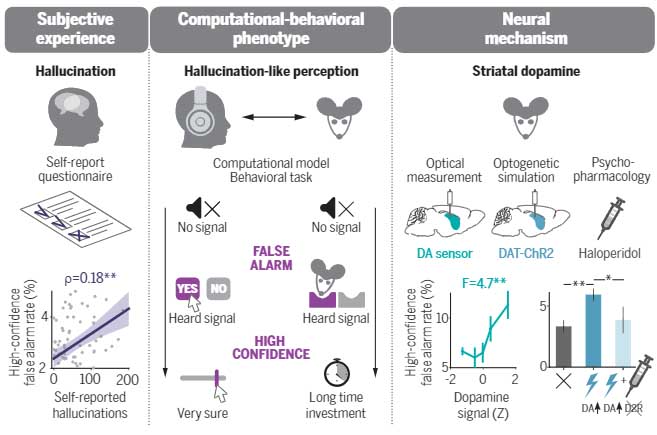

彼らはまず、マウスの幻聴を評価する系を確立し、幻聴を起こしやすいヒトでも同様の結果が出る事を確認しました。

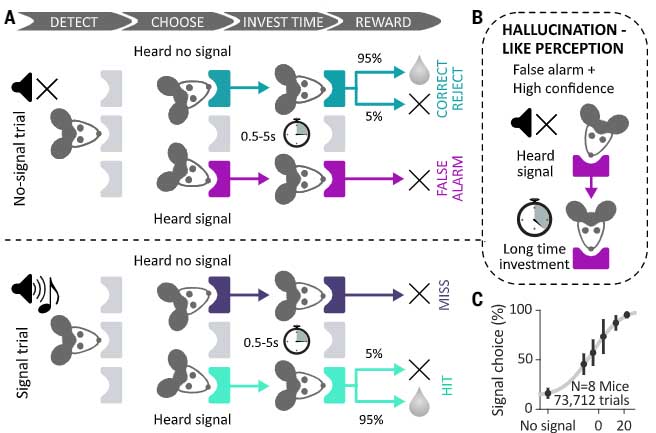

マウスには、まず40dBのバックグラウンドノイズの中に、トーンシグナルを聞かせるようにしました。

このトーンシグナルのボリュームを変化させながら、

「音が聞こえたらコッチ」「音が聞こえなかったらコッチ」

というように、違うポートを突くようにトレーニングし、

正解だったら報酬として95%の確率で水がもらえるようにしました。

もし、アラームが鳴っていないのにマウスが自信を持って「音が聞こえたポート」を突いていたら、それは幻聴が聞こえている、という判断です。

このマウスに、幻覚を誘発するケタミンを投与したところ、「偽アラーム」に反応した時間や回数等が明らかに増え、このマウス達は「幻聴」が聞こえているという可能性を示唆しました。

ヒトでも検証

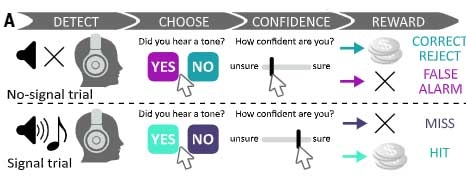

この現象が本当かどうか確認するため、幻聴を起こしやすい人達にも実験に参加してもらいました。

彼らには、日頃どれくらい幻覚を起こしやすいかアンケートをとり、その頻度と、「偽アラーム」への反応率を調べました。

結果、日頃の幻聴の頻度と、「偽アラーム」への反応率、自信の程、等に相関があり、この系はヒトでも機能することを確認しました。

幻聴が起こる前に、腹側線条体と線条体尾部のドパミン量が増加する

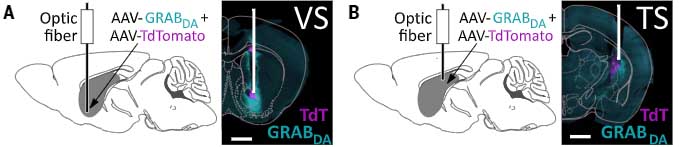

幻聴を評価するしっかりした系が確立できたので、彼らはこの系を使って、線条体のドパミン量と幻聴に関連があるかを調べました。

まず彼らは、腹側線条体と線条体尾部のドパミン量をGRABDAドパミンセンサーをAAVにのせて感染させ、

リアルタイムでドパミン量を定量できるようにしました。

その結果、同部位のドパミン量が高いと幻聴を起こしやすくなっていました。

また逆に、オプトジェネシスで線条体尾部のドパミン刺激を行うと、幻聴症状が増加しました。

以上の結果は、「線条体のドパミン量が増えると幻聴を起こしやすくなる」ことを示唆しており、

臨床的に「ドパミン量の増加が幻覚を誘発する」と考えられていたことの一部を、マウスの実験で証明することができました。

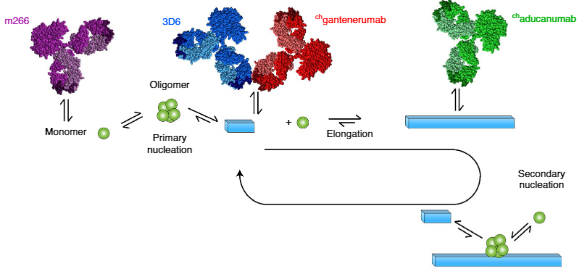

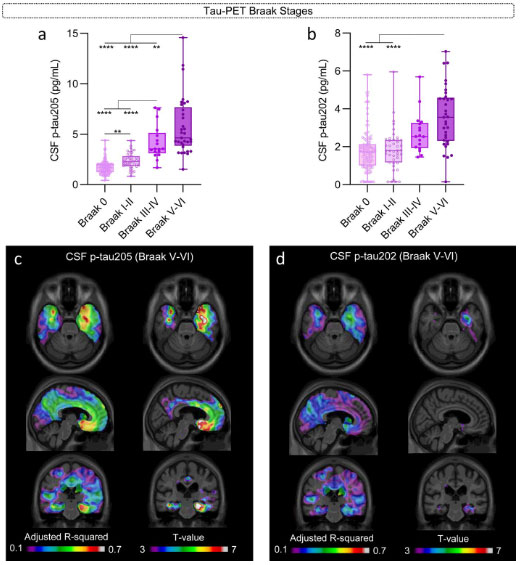

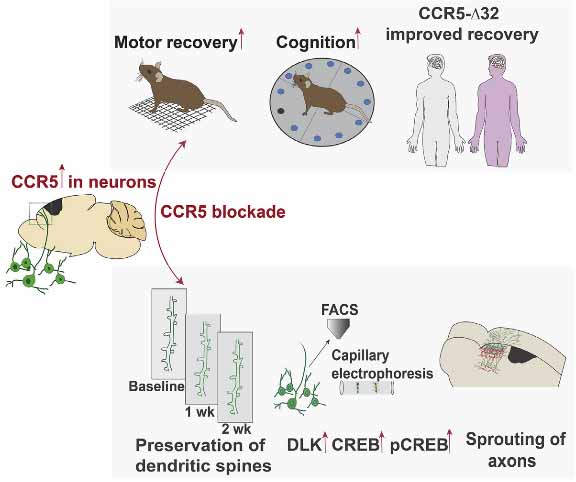

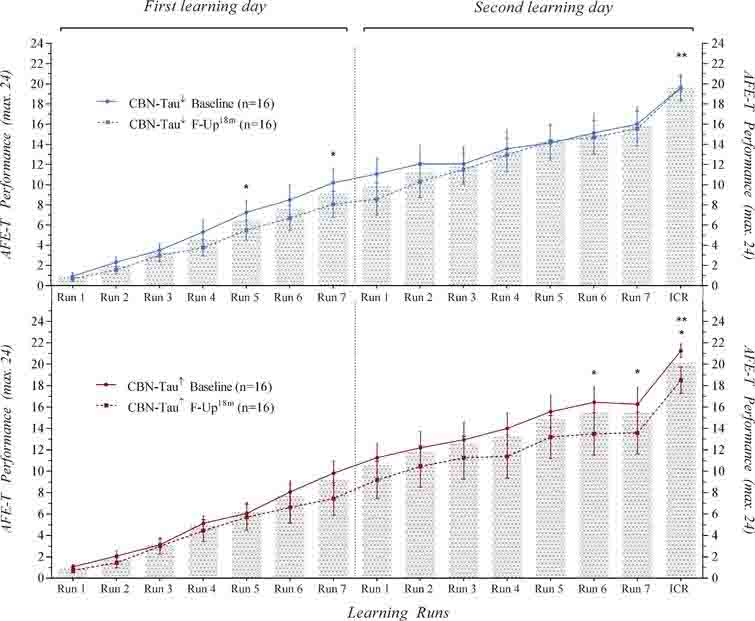

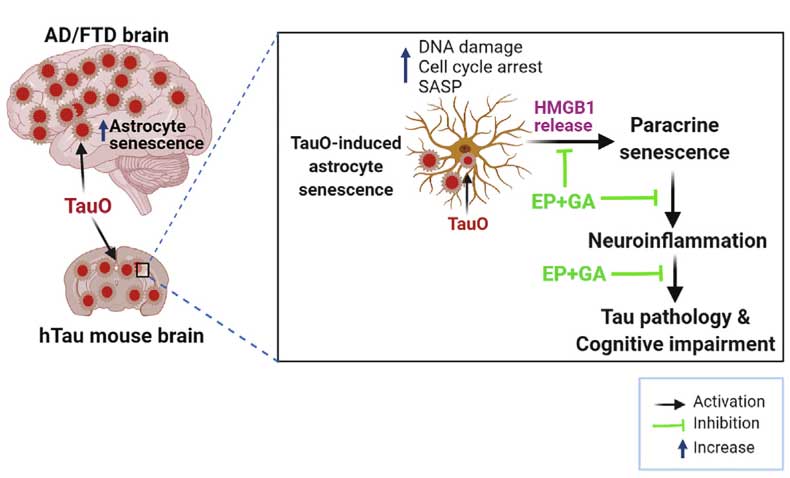

There has not been enough progress in our understanding of the basic mechanisms underlying psychosis. Studying psychotic disorders in animal models is difficult because the diagnosis relies on self-reported symptoms that can only be assessed in humans. Schmack et al. developed a paradigm to probe and rigorously measure experimentally controlled hallucinations in rodents (see the Perspective by Matamales). Using dopamine-sensor measurements and circuit and pharmacological manipulations, they demonstrated a brain circuit link between excessive dopamine and hallucination-like experience. This could potentially be useful as a translational model of common psychotic symptoms described in various psychiatric disorders. It may also help in the development of new therapeutic approaches based on anatomically selective modulation of dopamine function. Science , this issue p. [eabf4740][1]; see also p. [33][2] ### INTRODUCTION Psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia impose enormous human, social, and economic burdens. The prognosis of psychotic disorders has not substantially improved over the past decades because our understanding of the underlying neurobiology has remained stagnant. Indeed, the subjective nature of hallucinations, a defining symptom of psychosis, presents an enduring challenge for their rigorous study in humans and translation to preclinical animal models. Here, we developed a cross-species computational psychiatry approach to directly relate human and rodent behavior and used this approach to study the neural basis of hallucination-like perception in mice. ### RATIONALE Hallucinations are false percepts that are experienced with the same subjective confidence as “true” percepts. Similar false percepts can be quantitatively evaluated using a sensory detection task in which individuals report whether they heard a signal embedded in a background noise and indicate how confident they are about their answer. Thus, we defined hallucination-like percepts as confident false alarms—that is, incorrect reports that a signal was present, which are reported with high confidence. We reasoned that such experimentally controlled hallucination-like percepts engage neural mechanisms shared with spontaneously experienced hallucinations in psychosis and can therefore serve as a translational model of psychotic symptoms. Because psychotic symptoms are thought to involve increased dopamine transmission in the striatum, we hypothesized that hallucination-like perception is mediated by increased striatal dopamine. ### RESULTS We set up analogous auditory detection tasks for humans and mice. Both humans and mice were presented with an auditory stimulus in which a tone signal was embedded in a noisy background on half of the trials. Humans pressed one of two buttons to report whether or not they heard a signal, whereas mice poked into one of two choice ports. Humans indicated how confident they were in their report by positioning a cursor on a slider; mice expressed their confidence by investing variable time durations to earn a reward. In humans, hallucination-like percepts—high-confidence false alarms—were correlated with the tendency to experience spontaneous hallucinations, as quantified by a self-report questionnaire. In mice, hallucination-like percepts increased with two manipulations known to induce hallucinations in humans: administration of ketamine and the heightened expectation of hearing a signal. We then used genetically encoded dopamine sensors with fiber photometry to monitor dopamine dynamics in the striatum. We found that elevations in dopamine levels before stimulus onset predicted hallucination-like perception in both the ventral striatum and the tail of the striatum. We devised a computational model that explains the emergence of hallucination-like percepts as a consequence of faulty perceptual inference when prior expectations outweigh sensory evidence. Our model clarified how hallucination-like percepts can arise from fluctuations in two distinct types of expectations: reward expectations and perceptual expectations. In mice, dopamine fluctuations in the ventral striatum reflected reward expectations, whereas in the tail of the striatum they resembled perceptual expectations. We optogenetically boosted dopamine in the tail of the striatum and observed that increasing dopamine induced hallucination-like perception. This effect was rescued by the administration of haloperidol, an antipsychotic drug that blocks D2 dopamine receptors. ### CONCLUSION We established hallucination-like perception as a quantitative behavior in mice for modeling the subjective experience of a cardinal symptom of psychosis. We found that hallucination-like perception is mediated by dopamine elevations in the striatum and that this can be explained by encoding different kinds of expectations in distinct striatal subregions. These findings support the idea that hallucinations arise as faulty perceptual inferences due to elevated dopamine producing a bias in favor of prior expectations against current sensory evidence. Our results also yield circuit-level insights into the long-standing dopamine hypothesis of psychosis and provide a rigorous framework for dissecting the neural circuit mechanisms involved in hallucinations. We propose that this approach can guide the development of novel treatments for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. ![Figure][3] Hallucination-like perception framework and striatal dopamine. In humans and mice, a computational-behavioral task models hallucinations as high-confidence false percepts. In humans, such hallucination-like percepts are correlated with self-reported hallucinations. In mice, hallucination-like percepts are mediated by striatal dopamine. Data are means ± SEM. * P

Reference

- Schmack K, Bosc M, Ott T, Sturgill JF, Kepecs A. Striatal dopamine mediates hallucination-like perception in mice. Science. 2021 Apr 2;372(6537):eabf4740. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4740. PMID: 33795430.

こけでやっと責任部位が見つかりました、今後の新薬に期待がもてそうです。慶応大学や千葉大学も幻聴は線状体とにらんでたので、どちらかの病院で治療してもらいます。

面白いですね。fMRIで見たら視覚野の活動が上がったりするんでしょうか?幻覚でも。マウスでもfMRI可能な時代なのでやってみたら面白いかもですね。

確かにそうですね。

今回は幻聴をみているので、聴覚野のfMRIがどうなっているか気になりますね。(そう思って自分の記事を読み直したら、最初の方は幻視のイントロで始めていました。confusing な記事になっていてすみません。後で修正します。)

DLBの患者さんは幻視の訴えが多いですが、SPECTで後頭葉の血流は落ちているんですよね。

となると、一次感覚野の活動は落ちていて、連合野との connectivity に異常をきたしている可能性もありそうですね。

いずれにしても大変興味深いです。